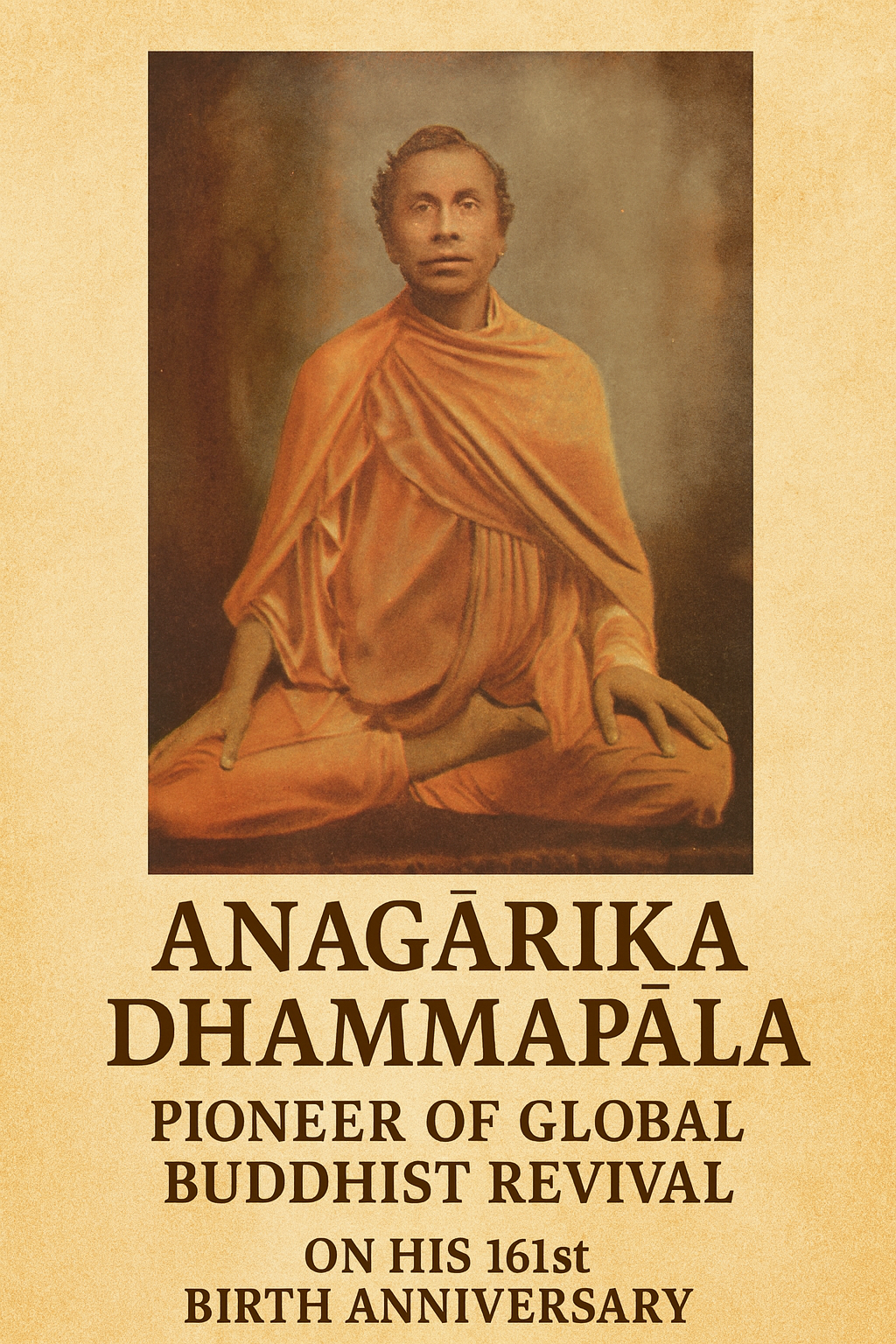

Anagārika Dhammapāla: Pioneer of Global Buddhist Revival | On His 161st Birth Anniversary

By Bhante Nivitigala Sumitta

On September 17, 1864, a child was born in Colombo, Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka), who would fundamentally transform the landscape of global Buddhism. Don David Hewavitharane, later known as Anagārika Dhammapāla, emerged as one of history’s most influential Buddhist revivalists, becoming the first global Buddhist missionary and a pivotal figure in the transmission of Buddhism to the Western world.¹

Early Life and Transformation

Born into a wealthy merchant family, David Hewavitharane was the son of Don Carolis Hewavitharana of Hiththetiya, Matara, and Mallika Dharmagunawardhana.² Despite his family’s Buddhist heritage, colonial pressures meant that David, like many Sinhalese children of his era, received a thoroughly Christian education. He attended prestigious missionary institutions including Christian College, Kotte; St. Benedict’s College, Kotahena; S. Thomas’ College, Mutwal; and the Colombo Academy (Royal College).³

By age nineteen, young Hewavitharane had mastered Christian theology and memorized more than half the Bible—knowledge he would later deploy to expose what he perceived as missionary hypocrisy.⁴ His transformation began dramatically in 1883 when Sri Lankan Catholics attacked a Buddhist procession. This incident prompted him to abandon his formal education and dedicate himself entirely to Buddhist study and practice.⁵

The Making of an Anagārika

The turning point in Hewavitharane’s spiritual journey came through his encounter with Colonel Henry Steel Olcott and Madame Helena Blavatsky, founders of the Theosophical Society. When they arrived in Ceylon in 1880, publicly taking refuge and precepts from a prominent Sinhalese bhikkhu, they catalyzed a Buddhist revival movement.⁶ Olcott’s subsequent efforts to establish Buddhist schools throughout Ceylon profoundly influenced the young man.

It was during this period that Hewavitharane adopted the name Anagārika Dhammapāla. The term “anagārika” (Pāli: “homeless one”) denoted his unique status between monk and layperson, while “dhammapāla” meant “protector of the Dhamma.“⁷ This nomenclature reflected his pioneering role as the first anagārika in modern times—a celibate, full-time worker for Buddhism who took the eight precepts for life, including refraining from sexual activity, eating after noon, and luxury.⁸

The Mahābodhi Mission

Dhammapāla’s most ambitious undertaking began in 1891 during a pilgrimage to Bodh Gayā, where he was appalled to discover the site of Buddha’s enlightenment under the control of Hindu priests and in a state of decay.⁹ This experience galvanized him to establish the Maha Bodhi Society, initially in Colombo in 1891, with offices moving to Calcutta in 1892.¹⁰

The Society’s primary objective was the restoration of Buddhist control over the Mahābodhi Temple at Bodh Gayā. Dhammapāla initiated a legal campaign against the Brahmin priests who had controlled the site for centuries.¹¹ Though the full restoration would not occur until 1949—sixteen years after his death—the movement he launched represented the first organized effort to reclaim Buddhism’s sacred geography.¹²

Global Buddhist Pioneer

Dhammapāla’s international prominence was established at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago in September 1893, where he represented “Southern Buddhism” (the contemporary term for Theravāda).¹³ His address on September 18, 1893, alongside presentations by Swami Vivekananda and Zen master Soyen Shaku, catalyzed the first wave of Western interest in Buddhism.¹⁴

In his Chicago presentation, titled “The World’s Debt to Buddha,” Dhammapāla strategically presented Buddhism in terms familiar to Western audiences, drawing parallels with science, the European Enlightenment, and Christianity, while subtly arguing for Buddhism’s superiority.¹⁵ He countered common Christian missionary portrayals of Buddhism as pessimistic and passive, instead presenting it as a “synthetic religion” and “system of life and thought” that offered both ethical guidance for ordinary people and profound metaphysical insights for serious students.¹⁶

Literary and Educational Contributions

Beyond his organizational work, Dhammapāla was a prolific writer and educator. Most of his extensive writings are preserved in *Return to Righteousness: A Collection of Speeches, Essays, and Letters of the Anagarika Dharmapala*, edited by Ananda Guruge and published in 1965.¹⁷ His works span theological treatises, comparative religion studies, and practical guidance for Buddhist living.

As founder and long-time editor of *The Maha Bodhi*, the journal of the Maha Bodhi Society, Dhammapāla regularly contributed articles to popular newspapers including *The Buddhist* and *Sinhala Bauddhaya*, counseling readers on leading meritorious lives.¹⁸ His English-language publications include seminal works such as “The World’s Debt to Buddha” (1893), “The Kinship between Hinduism and Buddhism” (co-authored with Henry S. Olcott, 1893), and numerous theological essays comparing Buddhism with Christianity and Western philosophy.¹⁹

Reviving Buddhism in India and Sri Lanka

Dhammapāla’s impact extended far beyond literary contributions. He pioneered the revival of Buddhism in India after nearly a millennium of virtual extinction, inspiring a mass movement among South Indian Dalits (including Tamils) to embrace Buddhism—anticipating B.R. Ambedkar’s neo-Buddhist movement by half a century.²⁰ His efforts also restored sacred sites: through his work, Kushinagar (the site of Buddha’s parinibbāna) once again became a major Buddhist pilgrimage destination.²¹

In Sri Lanka, Dhammapāla’s influence proved equally transformative. Working alongside Olcott, he helped establish over three hundred Buddhist schools, contributing to the revival of Theravāda Buddhism’s traditional stronghold.²² His advocacy for Buddhist nationalism provided intellectual foundation for subsequent Sinhalese political movements, including the Buddhist Revolution of 1956.²³

Final Years and Ordination

Throughout his career, Dhammapāla maintained his unique anagārika status, never formally ordaining under a senior bhikkhu despite decades of monastic-style living.²⁴ This changed only in his final year: at Sarnath in 1933, he was ordained as a bhikkhu, adopting the clerical name Sri Devamitta Dhammapāla.²⁵ The name “Devamitta” (“divine friend”) reflected both his global mission and his reverence for Heiyantuduwe Devamitta, a monk who had instructed him in his youth.²⁶

Dhammapāla died at Sarnath on April 29, 1933, aged 68. His final recorded words captured his lifelong commitment: “I would like to be reborn twenty-five more times to spread Lord Buddha’s Dhamma.“²⁷

Legacy and Impact

Anagārika Dhammapāla’s influence on modern Buddhism cannot be overstated. He was the first Buddhist in modern times to preach the Dhamma across three continents: Asia, North America, and Europe.²⁸ His innovative anagārika model provided a template for lay Buddhist practitioners worldwide, while his educational initiatives helped preserve and transmit Buddhist learning during a period of colonial suppression.

Today, Dhammapāla’s birthday anniversary is celebrated annually with lectures and cultural programs in Buddhist and Pāli educational institutions across Sri Lanka and India.²⁹ In 2014, both India and Sri Lanka issued commemorative postage stamps marking his 150th birth anniversary, and Colombo’s Anagārika Dhammapāla Mawatha (Anagārika Dhammapāla Street) honors his memory.³⁰

As we observe the 161st anniversary of his birth, Anagārika Dhammapāla’s vision of Buddhism as a global spiritual force continues to resonate. His pioneering work laid the foundation for Buddhism’s successful establishment in the West while simultaneously revitalizing the tradition in its Asian homelands. In an era of increasing global spiritual dialogue, his example of skillful adaptation—presenting ancient wisdom in contemporary terms without compromising essential teachings—remains profoundly relevant.

—–

References:

Richard Hughes Seager, *The World’s Parliament of Religions* (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995), 156.

Anagārika Dharmapāla, “Reminiscences of My Early Life,” in *Return to Righteousness: A Collection of Speeches, Essays, and Letters of the Anagarika Dharmapala*, ed. Ananda Guruge (Colombo: Government Press, 1965), 697-705.

Bhikkhu Sangharakshita, *Anagarika Dharmapala: A Biographical Sketch* (Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 1983), 15-18.

“Anagarika Dharmapala,” *Tricycle: The Buddhist Review*, February 7, 2016, https://tricycle.org/magazine/anagarika-dharmapala/.

Ibid.

Stephen Prothero, “Henry Steel Olcott and ‘Protestant Buddhism,’” *Journal of the American Academy of Religion* 63, no. 2 (1995): 285-290.

Ananda Guruge, ed., *Return to Righteousness: A Collection of Speeches, Essays, and Letters of the Anagarika Dharmapala* (Colombo: Government Press, 1965), introduction.

Alan Trevithick, *The Revival of Buddhist Pilgrimage at Bodh Gaya (1811-1949): Anagarika Dharmapala and the Mahabodhi Temple* (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2006), 89-95.

Sangharakshita, *Anagarika Dharmapala*, 45-50.

Trevithick, *Revival of Buddhist Pilgrimage*, 78-82.

Dipak Kumar Barua, *Buddha Gaya Temple: Its History* (Buddha Gaya: Temple Management Committee, 1981), 125-130.

Trevithick, *Revival of Buddhist Pilgrimage*, 245-250.

Seager, *World’s Parliament of Religions*, 154-158.

David L. McMahan, *The Making of Buddhist Modernism* (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 110-113.

Dharmapāla, “The World’s Debt to Buddha,” in *Return to Righteousness*, 3-24.

Dharmapāla, “The World’s Debt to Buddha,” 8-12.

Guruge, *Return to Righteousness*, preface.

“Anagarika Dharmapala: The Revered Buddhist Revivalist,” Tsem Rinpoche, October 20, 2018, https://www.tsemrinpoche.com/tsem-tulku-rinpoche/travel/anagarika-dharmapala-the-revered-buddhist-revivalist-and-writer-of-the-20th-century.html.

Dharmapāla, *Return to Righteousness*, table of contents.

Stephen Kemper, *Rescued from the Nation: Anagarika Dharmapala and the Buddhist World* (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 185-195.

Trevithick, *Revival of Buddhist Pilgrimage*, 180-185.

Prothero, “Henry Steel Olcott,” 295-298.

Steven Kemper, “The Nation Consumed: Anagarika Dharmapala and the Buddhist World” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, 2012), 220-235.

Bhadrajee Hewage, “Anagarika Dharmapala (1864–1933),” *St Andrews Encyclopaedia of Theology*, August 7, 2025, https://www.saet.ac.uk/Buddhism/AnagarikaDharmapala.

Ibid.

Hewage, “Anagarika Dharmapala.”

“Anagārika Dharmapāla,” *Tibetan Buddhist Encyclopedia*, accessed September 17, 2025, https://tibetanbuddhistencyclopedia.com/en/index.php/Anagarika_dhammapala.

“Anagārika Dharmapāla,” *Buddhism & Healing*, April 18, 2022, https://buddhism.redzambala.com/scholars/anagarika-dharmapala.html.“Anagarika Dharmapala—157th Birth Anniversary,” *LankaWeb*, September 17, 2021, https://www.lankaweb.com/news/items/2021/09/17/anagarika-dharmapala-157th-birth-anniversary.

“Anagarika Dharmapala,” *Detailed Pedia*, accessed September 17, 2025, https://www.detailedpedia.com/wiki-Anagarika_Dharmapala.